Film Review: High and Low (1963)

High and Low (1963)

[Tengoku to jigoku]

directed by Akira Kurosawa

Frames in this review are taken from the Criterion DVD released in 1998.

This is a series of two articles. The

second article compares this film with its source material, Ed

McBain’s detective novel King’s Ransom.

Akira Kurosawa is often mentioned in film critique as a Japanese director

who was too Western to be successful in his own country. This might seem

strange, for his best-known works are largely set in Medieval Japan —

Seven Samurai,

Rashomon

,

Yojimbo

. Some of them are based on works of Shakespeare,

but the the settings are unmistakably Japanese and the themes are surely

universal. In addition, several of his samurai adventures were later

remade into Hollywood or spaghetti westerns, but you can’t blame that on

him.

High and Low, one of his less well-known films, supplies an

explanation. Although it is set in bustling Tokyo, the film’s atmosphere

comes practically right out of film noir Los Angeles. There are

beachfront locations, remote hideaways, kidnapping plots, corporate power

plays over a company that makes women’s high heels, and even little kids

playing with cowboy hats and toy revolvers! What's more, the film is

based on an American crime novel, Ed McBain's

King's Ransom. Shakespeare in a Japanese setting is high art,

but adapting an American detective thriller?!

Still, the glaringly obvious American elements in the film are a bit of a

decoy, perhaps even a "Come get me" tease from Kurosawa. Only half of

the film is actually based on the novel. The other half of the film can

only be said to be generally inspired by film noir. High and

Low is as thorough a reworking of King's Ransom as

Dersu Uzala is of Arseniev's memoirs.

Plot

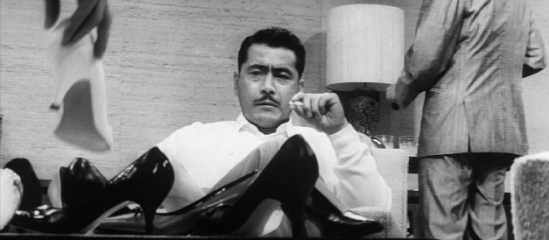

The film opens amidst corporate intrigue, as businessman Kingo Gondo (Toshiro Mifune) spars with fellow executives at National Shoes. The "old man" at the top of the company has been presiding over a slump in sales, and his subordinates have a plan to wow the public with stylish fashions, while also cutting costs by making shoes with cardboard and glue. The schemers need Gondo's sizeable share holdings to vote the old man out, but Gondo will have nothing to do with shoddy manufacturing. He's been with the company since the age of 16 and has worked his way up the ranks over a thirty-year career. Gondo shows the executives out the door, and then he sets in motion his own plan to take control of the company with a leveraged buyout of outstanding shares.

But after his son Jun goes outside to play with their chauffeur's son Shinichi, Gondo's plot is interrupted by a telephone call announcing his son's kidnapping and demanding a huge ransom for his release. Already heavily indebted, Gondo cannot afford to both pay the ransom and close the deal. But it turns out that the kidnapper has picked up the wrong boy, for Jun comes running back indoors and announces that he cannot find Shinichi. The kidnapper, however, puts Gondo in a moral crisis, calling again and demanding that Gondo pay the ransom anyway. Can Gondo bear to give up his dreams in shoe manufacturing, or will he be left with blood on his hands by refusing to pay the ransom?

In a normal mystery, what happens next would be fairly predictable. There'd be some clever plans to nab the kidnapper when the drop is made, followed by a stakeout, some shooting, and a happy ending. But Kurosawa is not one to blindly repeat formula. In High and Low, the tension is quickly released halfway through the film, as the ransom is paid and the kid is recovered. But that’s not the end. Instead, the police investigation then proceeds methodically, leading to a descent into Tokyo's underworld where they set a trap for the kidnapper.

Kurosawa films tend to be structured fairly formally. High and Low is divided into three very distinct parts. The events of the first part are confined almost entirely to one glass-enclosed room in Gondo's spacious hilltop house. In such confined quarters, the camerawork is methodical and the acting takes precedence. Toshiro Mifune carries the dignified authority of someone who is used to giving orders and being obeyed, leaving him frustrated by the impossible situation that he has been thrust into. His dutiful wife Reiko (Kyoko Kagawa) inject a dose of motherly compassion, insisting that her husband pay the ransom for the chauffeur’s boy.

Detective Tokura (Tatsuya Nakadai) is businesslike, professional, and calm in all situations. But a notable performance is also the one that’s least noticeable. It’s the chauffeur Aoki (Yutaka Sada), who is present throughout the kidnaping drama, yet fades into the background as other men take charge of his son’s safety. He’s not a titan of industry or a police detective; he’s just a chess piece in a complex game. Aoki only comes to the forefront when he tearfully pleads for his employer to pay his son's ransom. Throughout, he projects the sorrowful air of a defeated man, with head bowed, shoulders slumped, eyes darting around, and a tentative voice.

Bullet train

When the film leaves the staginess of Gondo’s house, it happens all of a sudden, as the Tokyo-Osaka bullet train wipes onto the screen with a loud blast of the horn. The onrushing scenery and the click-clack of the rails build up to a climax, as the unseen kidnapper changes the plan, giving directions to Gondo through a railphone and evading the trap that the policemen have set for him. The sequence is quite original and brings excitement into the film.

The investigation that follows is anticlimactic. Kurosawa's pace here can be be described as stately. A formalistic approach works well for the first part, with its stark moral choices and drastic consequences. But it turns the investigation into checkboxes on a list, proceeding smoothly (too smoothly) as the pieces fall into place one by one. Plus, the detectives are rather slower than the audience, for we’ve seen plenty of detective thrillers and can anticipate the plot points.

There is, however, one piece of detective work that isn’t so formulaic. Aoki feels duty-bound to help his employer recover his money, so he takes his son in the car to retrace his steps. Meanwhile, stocky Detective Bos'n Taguchi (Kenjiro Ishiyama) follows a different trail, and yet also arrives at the house where Shinichi was held captive. Here is the detective-work that had been missing from the rest of the investigation!

Descent

If part two has Kurosawa racking up strikes, then part three has him hitting a home run. The police set a trap for the kidnapper, and the film descends into the underside of Tokyo society. We visit noisy smoke-filled nightclubs inhabited by ugly Americans and corrupted Japanese, as well as eerie alleys where drug addicts wallow in misery. Finally, there’s a gripping encounter between the kidnapper and Gondo that the police watch with bated breath, hoping not to give away their presence. The condition of the heroin addicts is truly harrowing, more dead than alive, wracked by physical deformity, one of them scraping her nails on a shack as she struggles to pull herself up. Kurosawa probably didn't win many friends in Japan for this segment.

But this wholly original sequence gives the film a social awareness that would not be in a film that followed the novel more closely. A crime committed by habitual miscreants is one thing, but one committed by a hard worker clawing his way up from depravity makes a much different statement about upward mobility in the roaring economy of postwar Japan. There are several direct parallels to the chauffeur's situation, adding additional significance to Gondo's no-win scenario.

As the kidnapper tells Gondo over the phone, he practically dared the

kidnapping to happen by so conspicuously placing his shiny glass house at

the top of the hill. By paying the ransom, Gondo would be lifting one

man out of hard times and saving the life of a working man's son. This

is not to say that the kidnapper isn't cruel, however. His involvement

with the heroin addicts is more cruel than that of just a supplier, and

the connection to drugs was surely more shocking in 1963 than it is

today.

Continue to the second article, which contrasts the film with its source material, Ed McBain’s detective novel King’s Ransom.