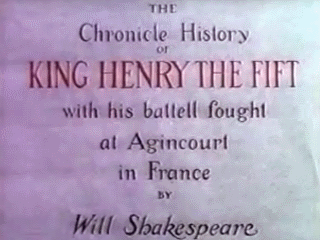

Film Review: Henry V (1944)

Henry V (1944)

directed by Laurence Olivier

Frames in this review are taken from the Criterion DVD.

Laurence Olivier's Henry Vis a vivid dramatization of Shakespeare and a great cinematic achievement. The young English King crosses the Channel, defeats the enemy, and returns to England with a French bride. Although France begins the play as the enemy, it ends up being joined to England by the bonds of matrimony. The film concludes with a shot their rings, Queen Katharine’s bearing the fleurs lis, and King Henry's both Plantagenet lions and fleurs de lis.

If this seem too simplistic a description of the relationship between

Britain and France, then that's simply a consequence of its function as

wartime propaganda. The film was shot and released during the Second

World War, as another great English-speaking host prepared to invade

France. The Soviet equivalent would be Eisenstein's

Ivan the Terrible, in which a ruthless Russian prince consolidates

Russia, fights a great patriotic war against the Mongols, and sends

envoys to Queen Elizabeth of England. Except that film presented Ivan’s

brutality in such a way that Stalin would be none-too-pleased.

In contrast, King George would surely approve of Olivier's Henry, a paragon of virtue and moral clarity. Shakespeare's Henry had excesses in his youth, but leaves them behind when he coldly scorns his old friend Falstaff. Olivier tones this down by having Henry's scorning words come in a distant voiceover at Falstaff's deathbed. Falstaff's tearful "God bless you, King Hal" then turns into the last words of an old man who'd once done wrong to the king, and has now reformed before death.

Likewise, Henry’s Britain is one happy family, Scots, Welshmen, and Englishmen joining in the common cause. Shakespeare's treason plot is missing from the film. There is no taint on Henry's invasion, for he never gives the order to kill all the prisoners after the battle. We can’t tarnish the image of brave little England, now can we? Just turn the archers into Spitfire pilots and the French knights into German bombers, and it all comes together.

It seems to be Olivier's Henry, rather than Shakespeare's, that

inspired Michael Shaara's Pulitzer Prize-winning historical novel

The Killer Angels. Shaara recounted the Battle of Gettysburg as the

American equivalent of Agincourt, populating his book with noble

characters on both sides of the battlefield. Similarly, Olivier's

Henry V has rid the English of their foibles. Blame for the

defeat is laid primarily at the hands of the Dauphin and his followers,

so that the French people, Queen Katharine, and Mountjoy come across as

reasonable people who are friendly towards England. In other words, they

are the true face of France, corrupted only by poor leadership. (Take

the Dauphin, replace him with Hitler.) The battle is the stuff of

legend, and the film is careful to point out the relevant features. For

example, we see unwieldy French knights in heavy armor being hoisted onto

their horses by rope-and-pulley, while limber English archers dart

to-and-fro.

An Elizabethan theater-going experience

These are not Hollywood stars sloppily mouthing Shakespearean lines to justify their star power on the marquee; these are experienced Shakespearean actors carrying out their lives’ work. The acting is so uniformly excellent that it's impossible to single out anyone for especial praise. The Archbishop is a windbag, the King of France is an absentminded old man, the Dauphin is an arrogant and cold-hearted rascal, Princess Katharine is mischievous and naïve, and the chorus narrator brings an authoritative presence to the stage. And that's not even counting the supporting characters like Pistol or Mountjoy, who get so much mileage out of their roles that they practically turn into major characters. The delivery is first-class, and a touch of rhythm distinguishes Olivier’s iabmic pentameter from the prose. The only jarring thing is the staunchly British pronunciations of all the French words: Calais (rhyme with palace), Dauphin (dolphin), Agincourt (pronounced t).

Even more fun for the viewer, the film bookends the main story with scenes at the Globe theater. Such a setting is very natural for the chorus structure of Shakespeare’s histories, and it is done with great vividness and splendor. We see the audience filing in, groundlings and gentlemen alike, hawkers selling their wares, actors preparing backstage. We get a good sense of the stage geography — curtains, proscenium, upper balconies. The actors move around and interact with the elements, placards are held up to announce scene changes, and a prompter sits onstage to follow along in the script. There’s even an April shower (well, the first of May) that comes in through the Globe's open roof, but the Show Must Go On.

The audience reaction is delightful, with uproarious laughter and

appreciative applause, along with incredulous heckling from the

groundlings. Theatergoers eat their snacks, a couple of cuddles are

seen, and rapturous theatergoers sit forward (or stand up) to read the

location placards.

Shakespeare in Love doesn't hold a matchstick to this recreation of

Elizabethan cinema. Love was too sanitized and too perfect,

while Henry's Globe theater feels real. The actors even deliver

their lines theatrically, switching to quieter motion picture style when

we enter the play within the play.

The Elizabethan music provides good atmosphere for the theatrical setting, and a mixture of choral and orchestral music creates an appropriately epic feel for the live-action film. The consistent use of the heraldic fanfare notifies the viewer when an important parley is about to take place. The camerawork is very dynamic, with lots of tracking and panning. There's a particularly breathtaking tracking shot from the side of the first French charge, as the horses slowly gather speed from a plod to a full gallop. It looks majestic.

Three-strip Technicolor brings out the heraldry of the Middle Ages, with the banners and bright costumes. Princess Katharine looks especially innocent with her rosy cheeks, maiden headwear, and pastel dresses. Played by 24-year old Renée Asherson, she looks much younger, younger even than the 19 that Catherine of Valois actually was when she married Henry V in 1420. When the film returns to the stage, however, Asherson looks more her age. The film plays the role of the “imaginary forces,” giving the on-location scenes a subtly different flavor from the stage scenes.

Technical

As Warner Brothers demonstrated with their ultra-resolution

The Adventures of Robin Hood and

Meet Me In St. Louis

, Technicolor can look incredible when the

separations are photographed separately and then recombined to full-color

digitally. Henry V doesn’t look anywhere near that good. The

transfer appears to have come from an Eastmancolor internegative, and so

the colors aren't quite faithful to the vividly saturated hues of

Technicolor. There's some convolutional fading causing the colors to

“breathe,” and the color timing doesn't always match from scene to

scene. Strangely enough, the final scene looks like it came from an

analog source, showing video noise that adds a screen door effect to the

formerly pristine digital picture. It doesn’t look like grain. What

happened?

There are also positive dust and white negative scratches (at spine number 41, this is before Criterion began digitally removing dust and scratches for their DVDs). Certainly, Criterion's transfer notes are suspicious: "This new digital transfer was created from a 35mm internegative, made from the YCM separation protection masters in England." YCM separations instead of Technicolor original negatives? That implies fourth-generation material (Technicolor original negative to interpositive to separations to the transfer interpositive that we're seeing). Perhaps it really is that far removed from the original negative. The focus looks soft even for Technicolor, but fortunately there's no visible fringing.

But this is nit-picking that most people won't notice. If economics didn't matter, every Technicolor film would be reregistered and retimed digitally. Henry V is reasonably well-preserved. The audio came off the optical (composite) negative, and it is sharp and clear except as already noted about the music. For a dialog-intensive film, this is what matters.

Henry V brings Shakespearean theater to life and is a Technicolor feast for the eyes. Just don't claim to have read the play after watching this film, because it is sufficient different that someone will catch you on it.